The Strategic Art of Saying No: How Positioning Creates Competitive Advantage

Strategy isn't just choosing what to do—but deliberately deciding what not to do.

In a business world obsessed with saying “yes” to more—more features, more markets, more opportunities—the most successful companies have mastered the strategic art of saying “no.” Their competitive advantage doesn't come from doing common things better than rivals, but from doing different things entirely.

Strategy has always been part of corporate culture, but Michael Porter's groundbreaking work transformed how we understand it today. While everyone talks about “strategy,” few grasp its essence: the deliberate design of a unique competitive position through a distinctive set of activities.

This essay explores Porter's fundamental strategic principles through a modern lens, examining how today's most successful companies—from Tesla to Trader Joe's, Costco to Canva—have applied these concepts to create sustainable competitive advantage in rapidly evolving markets.

1. Operational Effectiveness Is Not Strategy

In his landmark essay “What is Strategy?” published in the Harvard Business Review in 1996, Porter distinguished between doing things well—“operational effectiveness”—and doing things differently—“strategy.” This key distinction matters because eventually, every firm will catch up to best practices, causing companies to lose their competitive edge. Porter proposed an alternative approach: strategic positioning, which he describes as:

…attempts to achieve sustainable competitive advantage by preserving what is distinctive about a company. It means performing different activities from rivals, or performing similar activities in different ways.

Porter argues that three principles underlie strategic positioning:

Strategy is the creation of a unique and valuable position, involving a different set of activities.

Strategic positions emerge from three distinct sources:

- Serving few needs of many customers (Zoom focuses exclusively on video conferencing capabilities for a massive userbase)

- Serving broad needs of few customers (NetJets provides complete private aviation services exclusively to ultra-high-net-worth individuals and corporations)

- Serving broad needs of many customers in a narrow market (Shopify provides a complete e-commerce platform specifically for small to medium-sized independent businesses)

Strategy requires you to make trade-offs in competing—to choose what not to do.

Costco deliberately limits product selection (about 4,000 SKUs vs. 30,000+ at typical supermarkets), trades individual product margins for volume, and sacrifices store aesthetics and shopping convenience for lower prices.

According to Porter, trade-offs are at the heart of strategy. It's not about winning everything; it's about winning the specific market you decided to target.

Strategy involves creating “fit” among a company's activities.

Fit concerns how a company's activities interact and reinforce one another.

A modern example is Netflix, where content creation, recommendation algorithms, cross-platform technology, and global distribution work together. Data from viewing habits informs content creation, original content drives subscription growth, and the global platform amortizes content costs across a larger audience.

Fit drives both competitive advantage and sustainability: when activities mutually reinforce each other, competitors can't easily imitate them.

Quibi, one of the biggest venture-backed implosions of the zero-interest rate era, tried to imitate Netflix using mobile-first, short-form content reminiscent of TikTok. They cherry-picked elements from different successful business models rather than creating a coherent activity system where each element reinforced the others. They wanted Netflix's premium content and subscription revenue, but rejected its viewing flexibility and content volume. They wanted YouTube/TikTok's mobile-friendly short format, but rejected its user-generated content model and free access. They wanted HBO's prestigious talent relationships, but rejected its focus on destination viewing experiences. They raised $1.5B off the strength of their founders Jeffrey Katzenberg (founder of Dreamworks) and Meg Whitman (CEO of HP). They closed up shop 6 months after launch.

Porter argues that employees need guidance about how to deepen a strategic position rather than broaden or compromise it, extending the company's uniqueness while strengthening the fit among its activities. Leadership and strategy are inextricably linked because deciding which target group of customers and needs to serve requires discipline and communication.

2. Strategy Rests on Unique Activities

Porter's main argument is that competitive strategy is about being different. This means “deliberately choosing a different set of activities to deliver a unique mix of value.”

Apple and Android's businesses exemplify contrasting activities. Apple has a tightly integrated ecosystem, controlling both hardware and software while creating seamless integration across all their devices. This allows them to command premium pricing (60-100% higher margins than competitors), prioritize design and user experience over technical specifications, and generate significant revenue from services on top of their hardware ($96.2 billion in 2024, representing 25% of their total revenue).

In contrast, Google has an open Android platform, allowing other manufacturers to use their operating system on various hardware devices beyond their own Pixel line of phones, and pre-install Google Mobile Services (Play Store, Maps, YouTube, etc.) for a licensing fee. This maximizes the total number of users in their ecosystem, generating advertising and data collection opportunities. This open platform approach also allows them to sell services to developers globally, offering cloud, development, and analytics tools that generate revenue from the Android ecosystem.

Both models are remarkably successful based on Porter's definition of positioning:

Their specific set of activities which they either perform differently than rivals, or have a totally different set of activities that rivals don't or won't do.

3. How to Create Strategic Positioning?

Porter states that strategic competition can be thought of as “the process of perceiving new positions that woo customers from established positions or draw new customers into the market.”

In his view, strategic positioning is often not obvious, requiring creativity and insight. New entrants often discover unique positions that have been available all along but simply overlooked by established competitors.

However, the most common reason new positions open up is because of change:

New customer groups or new purchase occasions arise; new needs emerge as societies evolve; new distribution channels appear; new technologies are developed; new machinery or information systems become available. When such changes happen, new entrants, unencumbered by a long history in the industry, can often more easily perceive the potential for a new way of competing. Unlike incumbents, newcomers can be more flexible because they face no trade-offs with their existing activities.

A powerful example is the rise of Canva in a space dominated by Adobe for decades. Adobe focuses on professional designers with comprehensive powerful tools requiring significant expertise, whereas Canva positioned itself differently:

- Cloud-Native Design: Unlike Adobe's legacy of desktop software gradually transitioning to the cloud, Canva built its entire platform for browser-based collaboration from inception.

- Templates-First Approach: While Adobe provides powerful tools for creating from scratch, Canva prioritizes pre-designed templates and easy customization, reducing the skill required to produce professional-looking output.

- Pricing Model: Canva offers a robust free tier with gradual upgrades, contrasting with Adobe's higher-priced subscription model ($52.99/month for Creative Cloud).

- Team-Orientation: Canva built collaborative features into the core product, while Adobe's tools originated as single-user applications with collaboration added later.

- Asset Integration: Canva includes a vast library of stock photos, fonts, illustrations, and templates within the subscription price, while Adobe charges separately for stock assets through Adobe Stock and Adobe Fonts.

Types of Strategic Positioning

“Do one thing really well”

The first type of positioning is what Porter calls “variety-based positioning” which producing a subset of an industry's products or services rather than targeting customer segments and trying to do that better than anyone.

Trader Joe's: Few Exceptional Products at Exceptional Prices

Trader Joe's exemplifies through its deliberately curated product selection. While conventional supermarkets like Kroger or Safeway offer 30,000+ items across numerous brands, Trader Joe's focuses on approximately 4,000 items, with 80% under private labels. Their curation of a smaller set of Trader Joe's branded high-quality products positions them very differently than any other supermarket, with products that you can only get from their stores.

This positioning manifests through several interconnected activities:

- Product development focused on unique, high-quality items rather than multiple versions of the same product

- Smaller store footprints (10,000-15,000 sq ft vs. 50,000+ for conventional grocers) optimized for a curated selection

- Supply chain designed for direct sourcing and private label production

- Simplified operations with minimal technology and standardized store layouts

- Marketing emphasizing product discovery and quality rather than promotions

- Employee training centered around product knowledge and enhancing the shopping experience

This focused variety-based approach has enabled Trader Joe's to achieve industry-leading sales per square foot ($1,700 vs. $500-600 for traditional supermarkets) and exceptional customer loyalty. While competitors like Whole Foods continually expand their offerings in pursuit of different customer segments, Trader Joe's reinforces its strategic identity through disciplined curation.

“Full Service Offering for One Specific Customer”

The second type of positioning is what Porter calls “needs-based positioning” which targets a specific customer segment and aims to meet all or most of their needs, even if these customers could be served by other companies operating differently.

Porter highlights a critical element in needs-based positioning that's often overlooked:

Differences in needs will not translate into meaningful positions unless the best set of activities to satisfy them also differs. If that were not the case, every competitor could meet those same needs, and there would be nothing unique or valuable about the positioning.

What he means is that a company can't just proclaim that they serve or cater a specific type of customer, but that their approach must also be extremely specific in order to create a strong and defensible positioning.

Herman Miller: The design-forward furniture maker

Herman Miller has built its business around serving the comprehensive needs of design-conscious professionals and organizations who value workspace ergonomics, sustainability, and aesthetic excellence.

Rather than competing broadly in the office furniture market, Herman Miller positioned itself to meet multiple needs of this specific customer segment:

- Product development integrates human-centered ergonomic research with leading industrial designers and architects (collaborating with icons like Charles and Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi, and Yves Béhar)

- Manufacturing emphasizes cradle-to-cradle design principles with modular components that can be repaired, replaced, or recycled

- Design philosophy balances timelessness with innovation, creating pieces that maintain relevance and value for decades

- Workplace consulting services extend beyond furniture to comprehensive workspace design and employee wellbeing

- Warranty and service programs focus on longevity, with many signature products carrying 12-year warranties and repair services for vintage pieces

This positioning allows Herman Miller to command premium pricing while creating strong customer loyalty. Their comprehensive approach to serving design-conscious professionals—from ergonomic innovation to environmental stewardship to timeless aesthetics—creates a competitive advantage that conventional furniture manufacturers struggle to match. Their transparent sustainability practices, which include detailed environmental product declarations and zero-waste initiatives, further reinforce their authentic positioning with their target market.

“Reach customers in a unique way”

The third type of positioning is “access-based positioning.” According to Porter, this targets customers who are accessible in different ways, requiring a different set of activities to reach and serve them effectively, like a bank that mainly operates in rural areas, providing financial services to populations big banks typically ignore.

Example 1: Starlink, High-speed internet anywhere in the world

SpaceX's Starlink exemplifies access-based positioning by providing high-speed internet to customers who are geographically inaccessible to traditional broadband providers. Their entire business model is built around reaching these underserved users through a different configuration of activities:

- Network architecture uses low-Earth orbit satellites instead of ground-based infrastructure

- Terminal design focuses on user self-installation without technical expertise

- Pricing strategy balances affordability with the higher costs of satellite deployment

- Customer support systems operate entirely remotely through digital channels

- Regulatory approach navigates complex international telecommunications rules

By organizing around this access-based position, Starlink can charge premium prices ($110/month plus $599 equipment) while growing rapidly in rural areas, developing nations, and disaster zones where traditional providers cannot economically operate. Traditional telecoms companies are structured around density-dependent economics that make serving these customers unprofitable, creating the opening for Starlink's different approach.

Example 2: Stripe, Financial products for online businesses

Stripe positioned itself based on economic access, targeting developers and businesses who needed simplified payment processing but faced barriers from traditional banking systems. Their business is organized entirely around making payment infrastructure accessible:

- API-first architecture designed specifically for developers rather than finance professionals

- Documentation and implementation guides that prioritize clarity and ease of integration

- Pricing structure based on transparent transaction fees without setup costs or monthly minimums

- Global payment acceptance built-in from the start to serve international merchants

- Extensible platform approach allowing businesses to build customized payment flows

This access-based positioning allowed Stripe to build a business valued at over $95 billion by serving customers who found traditional payment processing technically inaccessible or prohibitively complex. Their entire activity system is optimized for connecting businesses to the financial system through developer-friendly interfaces, creating a unique position distinct from both conventional merchant accounts and consumer-focused payment solutions like PayPal.

Integration of Multiple Positioning Approaches (Most Powerful)

This integrated positioning creates an exceptionally strong competitive advantage because competitors must replicate the entire system of activities to achieve similar results.

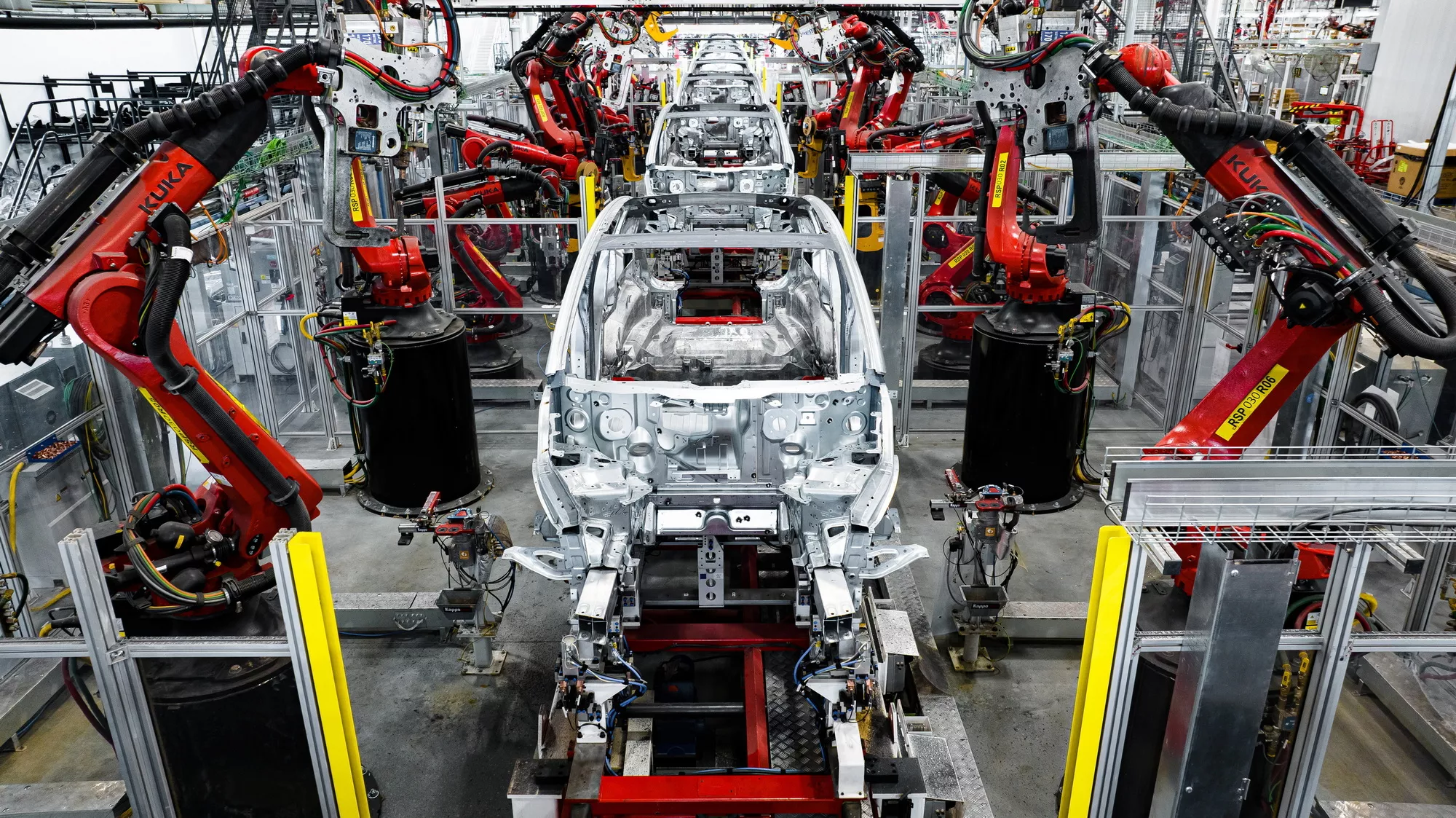

Tesla: The solar battery company that happens to build cars

Tesla exemplifies how integrating multiple positioning approaches creates a powerful competitive advantage.

Tesla's variety-based positioning centers on its exclusive focus on premium electric vehicles with specific technological characteristics:

- Battery and Powertrain Development: Unlike traditional automakers who outsource components, Tesla vertically integrated battery and powertrain development, building the Gigafactory to achieve economies of scale impossible when producing both electric and combustion vehicles.

- Software Engineering Emphasis: Tesla employs more software engineers than mechanical engineers, optimizing vehicles around electric architecture rather than adapting electric technology to conventional designs.

- Performance Prioritization: Tesla positioned electric technology as performance-enhancing rather than just environmentally friendly, reframing electric vehicles as performance superior rather than an environmental compromise.

Simultaneously, Tesla positioned itself to meet the comprehensive needs of environmentally-conscious, technology-forward luxury consumers:

- Integrated Energy Ecosystem: Tesla extended beyond vehicles to develop Solar Roof, Powerwall batteries, and energy management software, addressing their target customers' desire for comprehensive sustainability solutions.

- User Interface Design: Tesla centralized controls in a large touchscreen, appealing to tech-enthusiastic consumers who prefer software interfaces over traditional mechanical controls.

- Over-the-Air Updates: Tesla pioneered vehicles that improve over time through software updates, fundamentally changing the ownership experience from the traditional depreciation model.

Tesla's third dimension relates to access - creating entirely different ways for customers to purchase, maintain, and fuel their vehicles:

- Direct-to-Consumer Sales Model: Tesla bypassed the traditional dealer network, selling directly to consumers online and through company-owned showrooms.

- Supercharger Network: Tesla built its own charging infrastructure, creating a fundamentally different "refueling" experience addressing range anxiety and long-distance travel needs.

- Digital-First Ownership Experience: Tesla built the entire ownership journey around smartphone apps and digital interfaces rather than paper documentation and in-person interactions.

This multi-dimensional positioning creates advantages that competitors must comprehensively replicate rather than selectively imitate.

4. A Sustainable Strategic Position Requires Trade-offs

Porter argues that sustainable strategic positions require trade-offs—clear choices about what a company will not do. This principle remains one of his most powerful insights, yet it's often the most difficult for organizations to embrace in practice.

Porter identifies three fundamental reasons why trade-offs are essential:

- Inconsistencies in image or reputation - Companies cannot credibly serve contradictory customer needs simultaneously

- Different activities require different configurations - Activities optimized for one position often undermine performance in another

- Internal clarity and limits on coordination - Without clear trade-offs, organizations suffer from confused priorities and ineffective resource allocation

The Heightened Value of Clear Trade-offs

Making clear trade-offs is more valuable than ever:

- Customer Abundance of Choice means consumers can easily find specialized providers for specific needs. General providers trying to be "good enough" at everything increasingly find themselves outperformed by specialists in each category who have made clearer trade-offs.

- Supply Chain Complexity requires focused optimization to achieve excellence. Companies positioning themselves as sustainable, for instance, must make fundamental supply chain choices that conflict with positioning as the lowest-cost provider.

- Talent Specialization increasingly requires companies to optimize their culture, compensation, and work environment for specific types of talent rather than trying to appeal universally, forcing organizational trade-offs.

- Authenticity Premiums reward brands with clear identities and values. Modern consumers—particularly younger generations—are increasingly skeptical of brands claiming to be all things to all people, creating market penalties for positioning inconsistency.

Modern Exemplars of Strategic Trade-offs

Several contemporary companies demonstrate the power of clear trade-offs in establishing sustainable strategic positions:

Costco: The Disciplined Trade-off Master

Costco exemplifies disciplined trade-offs with decisions that might appear counterintuitive but reinforce their strategic position:

- Limited SKU Selection (~4,000 items vs. 30,000+ at typical supermarkets) sacrifices variety to achieve volume purchasing power and simplified operations

- Membership Fee Requirement turns away casual shoppers but creates predictable revenue and customer commitment

- Minimal Interior Aesthetics reduces costs while reinforcing the perception of value pricing

- Limited Online Presence maintains focus on the treasure-hunt in-store experience central to their model

- Employee Compensation Premium (~$24/hour average vs. industry ~$15) trades higher labor costs for lower turnover and better service

- Limited Delivery Options maintains operational simplicity and forces customer visits that drive impulse purchases

These trade-offs create a coherent system where each decision reinforces the others. Costco's gross margins (10-11% vs. Walmart's 24-25%) would be considered problematic for most retailers, but their trade-offs enable them to turn these thin margins into strong profitability through membership fees, operational efficiency, and high sales volume per SKU.

When Costco faces pressure to match competitors' digital offerings or expand selection, they consistently favor their strategic clarity over incremental growth opportunities. This disciplined approach has created one of retail's most sustainable competitive positions despite minimal technological advantage.

Failed Trade-offs: Cautionary Tales

The business landscape is littered with companies that attempted to avoid necessary trade-offs, often with disastrous results:

WeWork: The Refusal to Choose

WeWork's spectacular collapse from a $47 billion valuation to bankruptcy stemmed largely from its refusal to make clear strategic trade-offs:

- Attempted to be simultaneously a real estate company, a technology company, and a lifestyle brand

- Pursued contradictory goals of rapid growth and premium experience without reconciling the operational conflicts

- Expanded into residential housing, education, and fitness without resolving the fundamental economic challenges in their core business

- Claimed to be revolutionizing consciousness while operating a conventional arbitrage business model

- Positioned as both a community-focused organization and a profit-maximizing venture

This unwillingness to make clear choices about what WeWork would not do created fundamental inconsistencies that eventually collapsed under scrutiny.

5. The Integrated Systems Approach to Competitive Advantage

Three Types of Fit

Porter argues that while operational effectiveness can be imitated, true competitive advantage comes from the fit among a company's activities. He defines three distinct types of fit:

- First-order fit: Simple consistency between activities and overall strategy

- Second-order fit: Activities that reinforce one another

- Third-order fit: Optimization of effort through coordination and information exchange

GitLab: Remote-First Consistency

GitLab demonstrates first-order fit through complete alignment with its remote-work strategic positioning:

- Documentation Priority: Comprehensive written documentation of all processes and decisions

- Asynchronous Communication: Default to recorded videos and written updates over live meetings

- Global Compensation: Location-adjusted but globally competitive salary structure

- Handbook-First Culture: 12,000+ page public handbook documenting all company operations

- Transparent Decision-Making: Issues, roadmaps, and discussions conducted in public repositories

- Distributed Leadership: No centralized headquarters or management concentration

- Self-Service Onboarding: Structured process designed for minimal live assistance

- Results-Based Evaluation: Performance measurement based on output rather than activity

Every aspect of GitLab's operations consistently supports its fully-distributed organization model. There are no hybrid policies, headquarters privileges, or synchronous requirements that would contradict this positioning. This first-order fit has enabled GitLab to build a 1,500+ person global company with no offices.

Starbucks: Reinforcing Elements in the "Third Place" Experience

Starbucks demonstrates second-order fit through mutually reinforcing activities that collectively create its "third place" positioning:

- Real Estate Strategy selecting high-visibility, high-foot-traffic locations increases store visits

- Premium Store Design with comfortable seating encourages longer visits

- Extended Hours increase utilization of expensive retail locations

- Continuous Product Innovation creates reasons for repeat visits

- Mobile App Ordering reduces wait times, increasing visit frequency

- Loyalty Program collects customer data that improves product development

- Barista Training creates consistent experience that builds brand trust

- Employee Benefits (including education and healthcare) reduce turnover, improving service quality

These elements reinforce each other in powerful ways. The premium locations justify the higher-end store designs, which enable the premium pricing, which funds the employee benefits, which improves service quality, which supports the premium positioning. Each activity makes the others more effective.

Patagonia: The Responsible Supply Chain Optimization

Third-order fit represents the highest level of integration, where companies minimize redundancy and wasted effort through coordination and information exchange between activities.

Patagonia exemplifies third-order fit through extraordinary coordination that optimizes their responsible business model:

- Materials Traceability System tracking every component from source to finished product

- Environmental Impact Assessment informing both product design and marketing

- Repair Centers integrated with product development to identify recurring issues

- Worn Wear Resale Platform extending product lifecycles and reducing waste

- Fair Trade Certification integrated across manufacturing partners

- Transparent Supplier Relationships making factory conditions visible to consumers

- Grant Making aligned with environmental advocacy campaigns

- Employee Environmental Internship Program feeding insights back into product design

- Climate Action Investment coordinating emissions reductions across the value chain

This system minimizes environmental impact through unprecedented coordination. Patagonia's designers receive data from repair centers to improve durability, supplier relationships are optimized around fair labor practices rather than just cost, and marketing is integrated with environmental storytelling based on verified supply chain data. Their entire business model demonstrates how activity coordination can simultaneously serve business, environmental, and social objectives.

6. The Modern Strategic Leader: Expanding on Porter's Leadership Framework

Porter addresses the crucial role of leadership in creating and maintaining strategic positioning. He identifies several key leadership responsibilities:

- Clearly communicating the company's unique position

- Making trade-offs explicit

- Forging fit among activities

- Maintaining organizational discipline and continuity

Porter argues that while operational effectiveness can be delegated to management layers, strategy formulation and implementation require direct leadership involvement. The leader's primary role is to define the strategic position, make necessary trade-offs explicit, and ensure that the organization's activities reinforce each other over time.

Modern Leadership Exemplars: Creating and Maintaining Strategic Positioning

Satya Nadella at Microsoft: Transformational Strategic Clarity

When Satya Nadella became CEO of Microsoft in 2014, the company was struggling with strategic confusion, competing internal priorities, and declining relevance in key markets. Nadella's leadership approach illustrates several aspects of Porter's framework applied to transformation:

Position Definition: Nadella articulated a clear new position for Microsoft as a “cloud-first, mobile-first” company, and later refined it to “intelligent cloud and intelligent edge.” This clarity replaced the previous diffuse focus on protecting Windows.

Making Trade-offs Explicit: Nadella made difficult trade-offs visible by:

- Writing off the $7.6 billion Nokia acquisition to exit the consumer mobile hardware business

- Bringing Office to competing platforms like iOS and Android

- Shifting from perpetual licenses to subscription models despite short-term revenue impacts

- Embracing open source after decades of opposition

Creating Fit Among Activities: Nadella realigned Microsoft's activities to support the new strategic position:

- Reorganized the company around cloud services rather than product divisions

- Revised compensation structures to reward cloud adoption metrics

- Rebuilt the developer relations approach to support multi-platform development

- Redirected acquisition strategy toward cloud-supporting technologies (GitHub, LinkedIn)

- Reshaped culture to emphasize growth mindset and collaborative innovation

Maintaining Strategic Continuity: While transforming the company, Nadella maintained continuity in Microsoft's enterprise focus and productivity expertise, evolving rather than abandoning the company's core strengths.

The results of this leadership approach have been extraordinary—Microsoft's market value increased from approximately $300 billion when Nadella took over to over $2.5 trillion today. More importantly, the company regained strategic coherence and relevance in core markets.

What makes Nadella's example particularly instructive is how he applied Porter's leadership principles to transformation rather than mere maintenance of an existing position. He demonstrated that strategic leadership can successfully reposition an organization without abandoning the concept of a coherent, focused strategy.

A Call to Strategic Courage

Perhaps the most important lesson from both Porter's original framework and contemporary examples is that strategy ultimately requires courage—the courage to make clear choices, accept deliberate limitations, and pursue genuine distinctiveness in a world that often rewards conformity.

The essence of strategy design is not creating elaborate plans or adopting the latest management trends, but making and sustaining the difficult choices that define what an organization stands for and how it creates unique value.