How to Build The Future: Lessons from Zero to One

The term “zero to one” has become so common that it's lost its meaning. But analyzed in-depth, it has valuable lessons for startup builders.

Introduction

The term “zero to one,” a popular term in startup circles, has become so common that the original intent has seemingly lost its meaning. If everything was actually “zero to one,” society would be far more advanced than it is today with most of society's problems decreasing at an exponential rate. Not to mention, it's extremely hard and unintuitive to build something that's actually zero to one.

It's one of those labels that have become a signaling technique, but ironically, it has kind of become a tell: anyone who claims to be doing “zero to one” work out loud is likely not building something that is “zero to one.” It's literally written in the book that it ought to be a secret.

This post will unpack the book and what I thought are the most salient pieces of advice for builders.

I. What does “zero to one” actually mean?

The term “zero to one” was popularized by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, first in his Stanford class CS183B: Startups, then eventually as a book published with one of his students in the class, Blake Masters, who shared his notes from the class in a Tumblr blog. They titled it Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future.

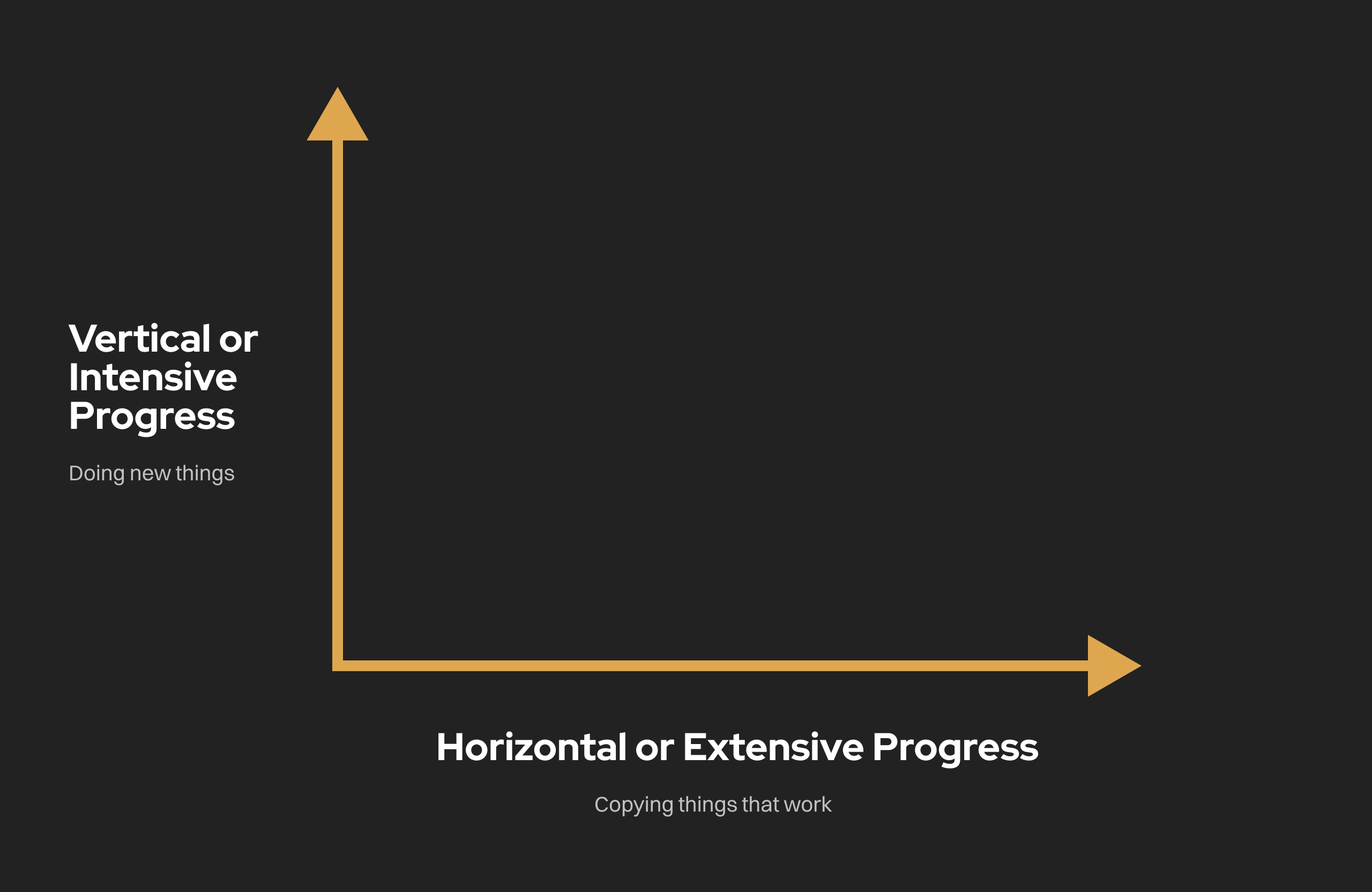

To go from zero to one means to produce vertical or intensive progress. To create entirely new things, new markets, new systems, a new way of doing things that were not seen or done before.

To quote Thiel:

Vertical or intensive progress means doing new things—going from 0 to 1. Vertical progress is harder to imagine because it requires doing something nobody else has ever done. If you take one typewriter and build 100, you have made horizontal progress. If you have a typewriter and build a word processor, you have made vertical progress.

It's the opposite of one of n, or horizontal progress, which is copying things that we know already work. He calls horizontal progress “globalization”—taking things that work somewhere work elsewhere, and vertical progress “technology” which is a new and better way of doing things.

The Contrarian Question

This zero to one idea is spurred by the contrarian question: What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

Thiel likes this question because it's intellectually and psychologically difficult: it must be something that's not already agreed upon and be something that's known to be unpopular. A good answer to this question is what he believes can actually change the future in a way that's rooted in today's world.

This is important because philosophically, Thiel considers technological progress as a moral imperative, a way to prevent destruction because globalization is unsustainable.

He expands on this by using a thought exercise: if China doubles its energy production, it will double the air pollution, and if India lived the same way Americans did, it would be environmentally catastrophic for the world. Thus, in a world with scarce resources, globalization without technology is unsustainable.

Whether you believe that mental exercise is up to you. The lesson here is that there is a logical conclusion to maintaining the status quo, and technology has the ability to alter its course.

Why startups?

He makes a case that startups have the best chance of changing the world for the better (and uses the Founding Fathers of the United States and the Traitorous Eight of Silicon Valley as examples).

The reason is because: 1) they are bound together by a sense of mission, and 2) it's too hard and too slow to do in large organizations or by yourself. Bureaucracies move too slow, are risk-averse, and it's common to signal that work is being done for the sake of career advancement while not actually moving the needle in any meaningful way. Whereas in startups, you can move quick, and most importantly, you can think:

Positively defined, a startup is the largest group of people you can convince of a plan to build a different future. A new company’s most important strength is new thinking: even more important than nimbleness, small size affords space to think.

Lessons learned

Thiel, having been the CEO of PayPal, observed that after the dot-com bubble there were some lessons that ended up becoming dogma in Silicon Valley:

- Make incremental advances

- Stay lean and flexible

- Improve on the competition

- Focus on product, not sales

But he argues that the opposite of these principles are probably more correct:

- It is better to risk boldness than triviality.

- A bad plan is better than no plan.

- Competitive markets destroy profits.

- Sales matter just as much as product.

These become the foundational tactics in the book.

II. Building Monopolies

The business version of the contrarian question is, "What valuable company is nobody building?"

This is an important because building a valuable company means you not only create value; you must also capture value in return. And truly valuable companies are not building undifferentiated businesses which charge what the market determines.

Rather, the truly valuable companies are monopolies—so good at what they do that no other company can offer a substitute. Because they are unique, they can set the price and can command outsized profits.

Thiel uses this as a central point: that monopoly is the opposite of competition, because under perfect competition, all profits get competed away:

The lesson for entrepreneurs is clear: if you want to create and capture lasting value, don’t build an undifferentiated commodity business.

For example, SpaceX was clearly a differentiated company when it was founded—they believed in lowering the cost of rocket launches through vertical integration and building reusable rockets. But no one believed they could do it because it's never been done before let alone by a private company.

Thiel goes a step further to state that competitive businesses have a problem beyond loss of profits—that to survive, they push people toward ruthlessness. Therefore, becoming a monopoly business isn't just necessary for survival, it's the only way for companies to be able to think long-term:

In business, money is either an important thing or it is everything. Monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money; non-monopolists can’t. In perfect competition, a business is so focused on today’s margins that it can’t possibly plan for a long-term future.

Only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits.

He argues that creative monopolies—those that create new products that benefit everybody and sustainable profits for the creator—are incentivized to drive progress because they can can command years if not decades of monopoly progress. And they can keep innovating because they have profits that enable them to make long-term plans and finance ambitious research. To take it a step further, Thiel states:

...every business is successful exactly to the extent that it does something others cannot. Monopoly is therefore not a pathology or an exception. Monopoly is the condition of every successful business.

He summarizes the monopoly vs. competition dichotomy as such:

All happy companies are different: each one earns a monopoly by solving a unique problem. All failed companies are the same: they failed to escape competition.

III. Last Mover Advantage

Great companies are not just about becoming a monopoly but staying one, and that means that it needs to generate cash flows in the future. Thiel emphasizes this because he thinks there is a "measurement mania" on short-term metrics; people remember growth but miss the second piece: endure.

There's nothing inherently wrong with targets but he argues that they can make someone miss the most important question you should be asking:

Will this business still be around a decade from now?

He argues that numbers alone won't tell the story; it's about the qualitative characteristics of the business—what makes it a monopoly.

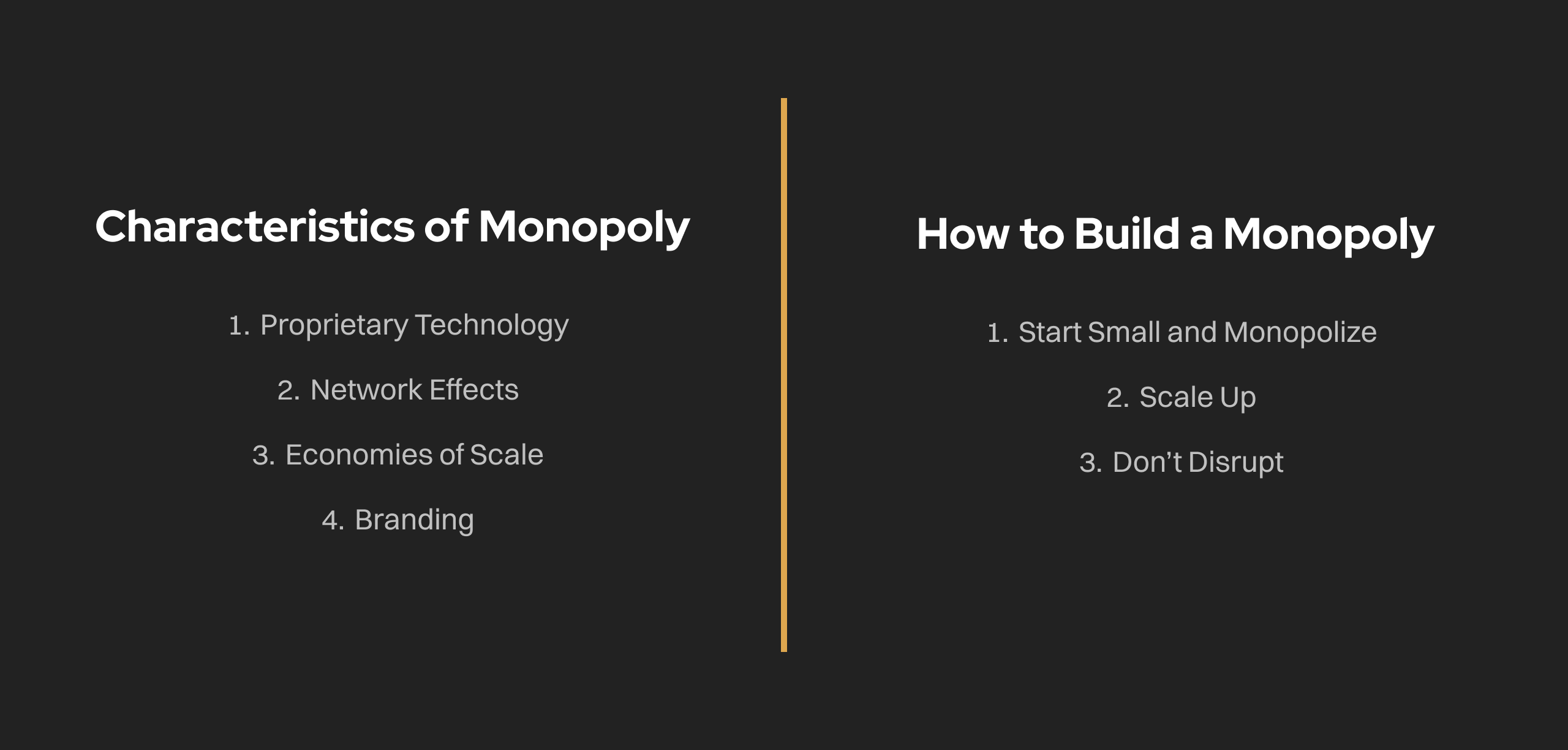

Characteristics of a monopoly

For a company to endure and generate cash flows in the future, they need at least or ideally a combination of these:

- Proprietary Technology

- This is a system, tool, or application that belongs exclusively to an enterprise, thus making it extremely difficult or impossible to replicate. For proprietary technology to have any true monopolistic advantage, it must be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute in an important dimension. You either create something totally new, make an existing solution 10x better, or 10x improvement through superior design.

- Network Effects

- Network effects is when something becomes more valuable as more people use it. For example, social networks are only valuable because everyone else is in it. There's also multi-sided network effects that are common in marketplaces: Uber is valuable as a ride-hailing company because that's where riders are, and riders are there because that's where drivers are.

- Economies of Scale

- A monopoly gets stronger as it gets bigger: when fixed costs can be spread out over greater quantities of sales. This is prevalent especially in software companies where the marginal cost of producing another copy is zero.

- A good startup should have the potential for scale built into its design.

- Branding

- Branding can be powerful because it resonates with customers at an emotional level making it more likely to choose them over competitors. Strong brands command premium pricing and customer loyalty, and create can create sustainable advantages by reinforcing the brand's values on every customer touchpoint.

- Apple is commonly used as having a strong brand, which is true, but it also has proprietary technology, network effects, and economies of scale. No technology company can be built on brand alone, and beginning with brand rather than on substance is dangerous.

Meta (formerly Facebook) demonstrates how network effects can create an unassailable monopoly position. The more people joined, the more valuable it became for others to join, creating the kind of virtuous cycle Thiel identifies as crucial for monopolies. Their acquisition strategy (Instagram, WhatsApp) showed deep understanding of how to maintain monopolistic positions in social networking as technology evolved.

How to build a monopoly

Characteristics of a monopoly matter, but to get them to work, you need to choose the market carefully and expand deliberately.

- Start Small and Monopolize

- “Every startup is small at the start. Every monopoly dominates a large share of its market. Therefore, every startup should start with a very small market. Always err on the side of starting too small. The reason is simple: it’s easier to dominate a small market than a large one. ”

- “The perfect target market for a startup is a small group of particular people concentrated together and served by few or no competitors. Any big market is a bad choice, and a big market already served by competing companies is even worse.”

- Scaling Up

- “Once you create and dominate a niche market, then you should gradually expand into related and slightly broader markets. Amazon shows how it can be done. Jeff Bezos’s founding vision was to dominate all of online retail, but he very deliberately started with books. There were millions of books to catalog, but they all had roughly the same shape, they were easy to ship, and some of the most rarely sold books—those least profitable for any retail store to keep in stock—also drew the most enthusiastic customers.”

- “Sequencing markets correctly is underrated, and it takes discipline to expand gradually. The most successful companies make the core progression—to first dominate a specific niche and then scale to adjacent markets—a part of their founding narrative.”

- Don't Disrupt

- “The concept was coined to describe threats to incumbent companies, so startups’ obsession with disruption means they see themselves through older firms’ eyes. If you think of yourself as an insurgent battling dark forces, it’s easy to become unduly fixated on the obstacles in your path. But if you truly want to make something new, the act of creation is far more important than the old industries that might not like what you create. Indeed, if your company can be summed up by its opposition to already existing firms, it can’t be completely new and it’s probably not going to become a monopoly.”

- “As you craft a plan to expand to adjacent markets, don’t disrupt: avoid competition as much as possible.”

IV. You are Not a Lottery Ticket

Is the future a matter of chance or by design? Thiel advices to think of the future as something that ought to be influenced rather than something that is indefinite and randomly uncertain.

Can you control your future?

In Thiel's view:

...a definite person determines the one best thing to do and does it. Instead of working tirelessly to make herself indistinguishable, she strives to be great at something substantive—to be a monopoly of one. This is not what young people do today, because everyone around them has long since lost faith in a definite world.

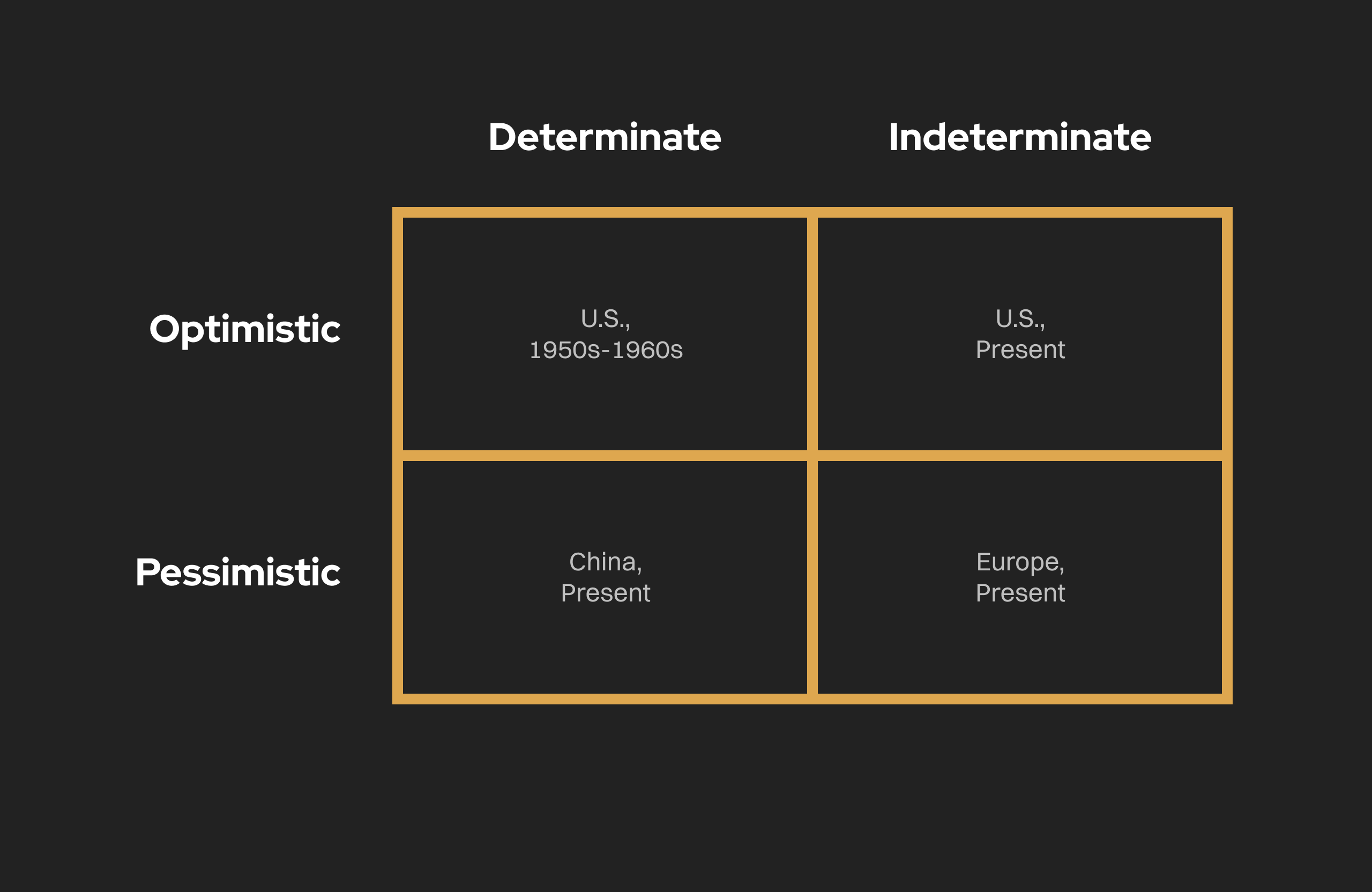

Thiel breaks this down into a 2x2 matrix. Starting from the bottom left:

- Indefinite Pessimist

- Someone who looks onto a bleak future, but has no idea what to do about it.

- Definite Pessimist

- Someone who believes the future can be known, but since it will be bleak, he must prepare for it.

- Indefinite Optimist

- Someone who thinks the future will be better, but he doesn't know how exactly, so he won't make any specific plans.

- Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already-invented ones.

- Definite Optimist

- Someone who thinks the future will be better than the present if he plans and works to make it better.

- To bring this point home, Thiel uses examples of visionaries with bold plans: how the Empire State Building was built in 2 years, the Golden Gate Bridge was finished in 4 years, the Manhattan Project produced the first nuclear bomb in 4 years, the Interstate Highway System connected the United States in less than 10 years, the Apollo Program which started in 1961 put 12 men on the moon before it finished in 1972. He argues that few have grand visions that are definite anymore.

The Return of Design

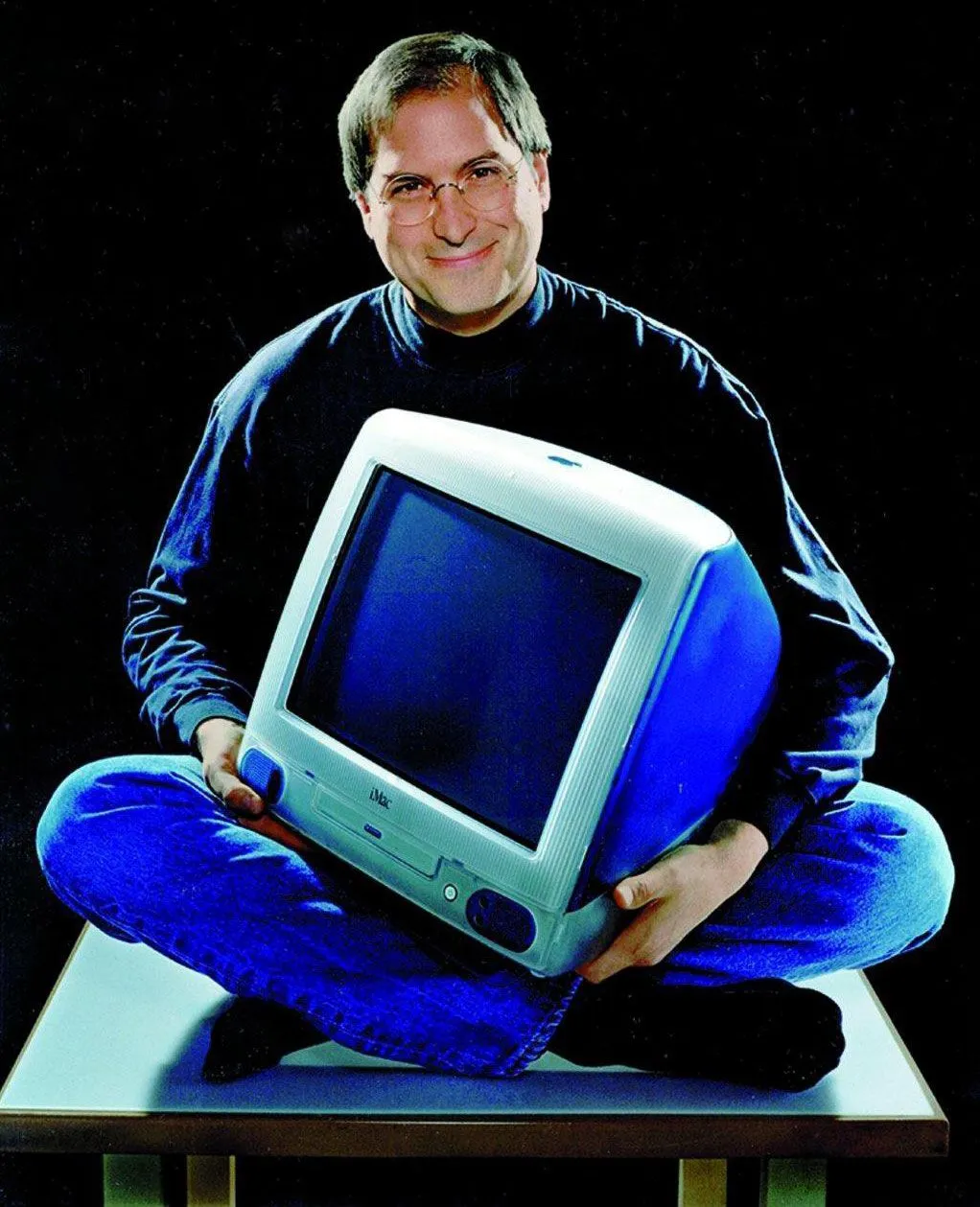

Every great entrepreneur is first and foremost a designer. To Thiel, the most important lesson from Steve Jobs has nothing to do with his aesthetics, but everything to do with his business—“Apple imagined and executed definite multiyear plans to create new products and distribute them effectively.” And he did this through careful planning and not by listening to focus groups or copying others' successes.

Long-term planning is often undervalued in our short-term world.

Thiel ends this chapter with this banger:

A startup is the largest endeavor over which you can have definite mastery. You can have agency not just over your own life, but over a small and important part of the world. It begins by rejecting the unjust tyranny of Chance. You are not a lottery ticket.

V. Follow the Money

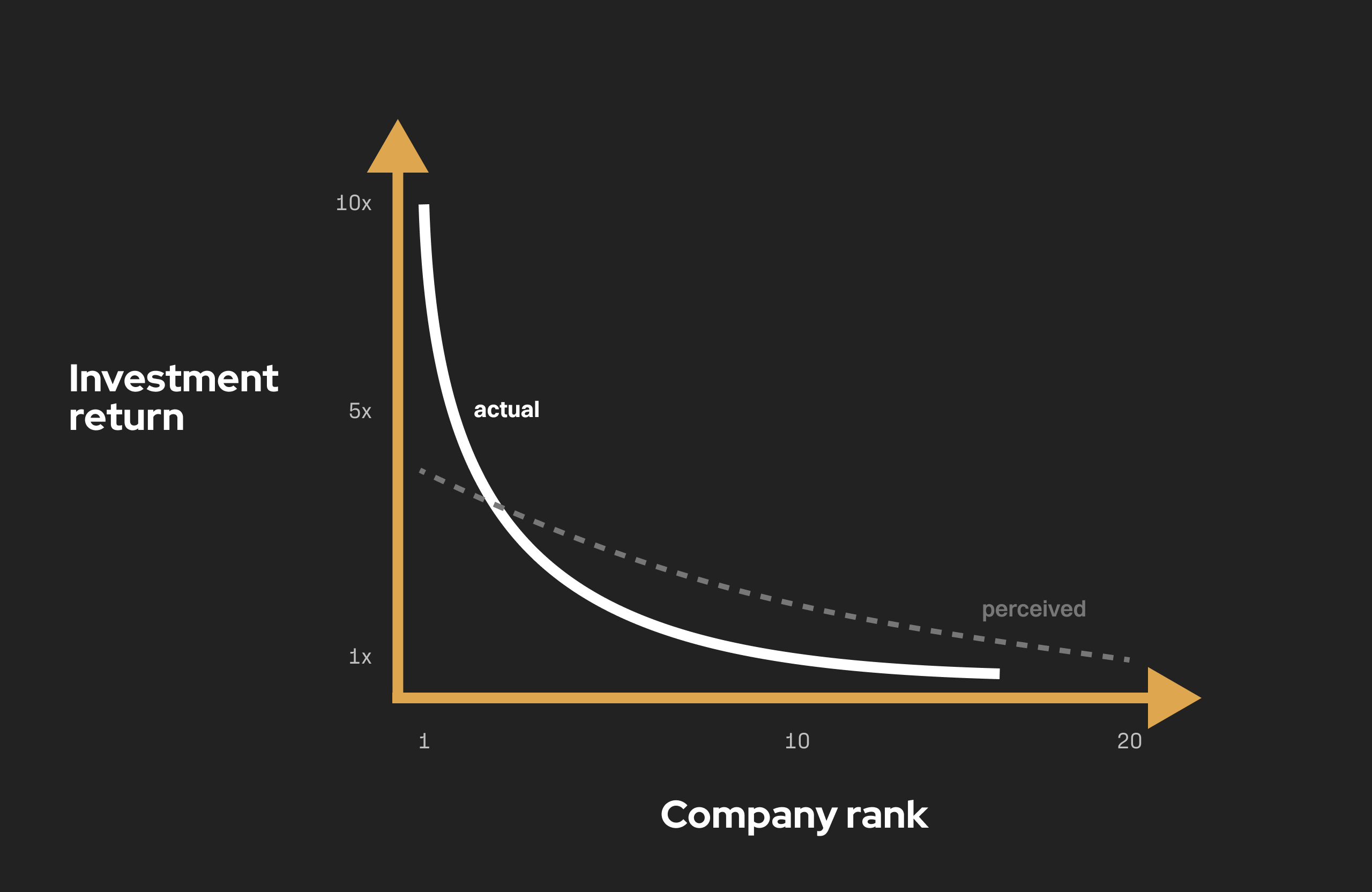

There are two main points of this chapter: 1) never underestimate exponential growth, and 2) we don't live in a normal world; we live under a power law. To contextualize this for startups: monopoly businesses capture more value than millions of undifferentiated competitors.

The Power Law of Venture Capital

Thiel explains how the power law is underestimated even in venture, a business built entirely on finding outliers. The general thinking is that venture returns are normally distributed—bad companies fail, mediocre ones flail, and good ones return 2x or 4x, when instead it follows a power law: a small handful of companies radically outperform all others.

He argues that this is a mistake: that focusing on diversification instead of a single-minded pursuit of the very few companies that can be overwhelmingly valuable will make you miss the rare companies in the first place.

What this means for venture capitalists:

Every single company in a good venture portfolio must have the potential to succeed at vast scale. [...] Once you think you're playing the lottery, you've already psychologically prepared yourself to lose.

What to Do With The Power Law

To bring this point home, Thiel contextualizes the power law isn't just for investors, but it's important to everybody because everybody is an investor: choosing a career is acting on a belief that the kind of work you do will be valuable decades from now.

He's against diversified portfolios of any kind that follow the sentiment “Don't put all your eggs in one basket.” Even the best investors have a portfolio, but investors who understand the power law make as few investments as possible.

He doubles-down on this:

But life is not a portfolio: not for a startup, and not for any individual. An entrepreneur cannot “diversify” herself: you cannot run dozens of companies at the same time and then hope that one of them works out well. Less obvious but just as important, an individual cannot diversify his own life by keeping dozens of equally possible careers ready in reserve.

[...] It does matter what you do. You should focus relentlessly on something you're good at doing, but before that you must think hard about whether it will be valuable in the future.

And contrary to what most people think about this book, Thiel is actually against the idea that there should be more companies that are started exactly because the power law goes against it:

For the startup world, this means you should not necessarily start your own company, even if you are extraordinarily talented. If anything, too many people are starting their own companies today. People who understand the power law will hesitate more than others when it comes to founding a new venture: they know how tremendously successful they could become by joining the very best company while it's growing fast. The power law means that differences between companies will draft the differences in roles inside companies.

However, for the brave few who do start companies, the advice of the power law remains: that most important things are singular — one market will probably be better than others, one distribution strategy dominates all others, and some moments matter far more than others:

What's most important is rarely obvious. It might even be a secret.

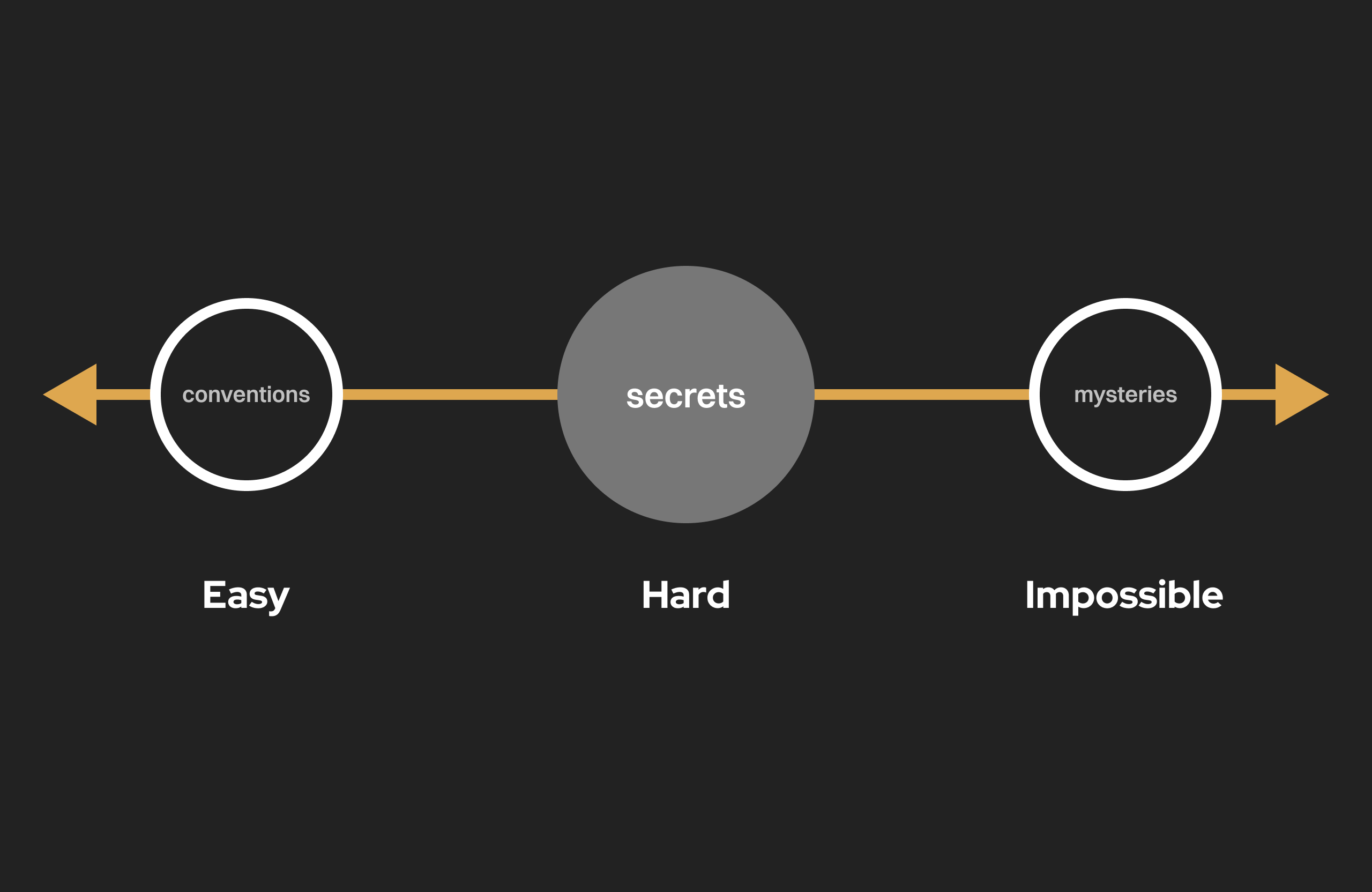

VI. Secrets

One of the main points of the entire book is that every one of today's ideas was once unknown and unsuspected. Conventional truths may be important, but they won't give you an edge, because it's not a secret.

Returning to the business version of the contrarian question—what valuable company is nobody building?—Thiel argues that every correct answer is necessarily a secret: something important and unknown, something hard to do but doable.

If there are many secrets left in the world, there are probably many world-changing companies yet to be started.

Why Aren't People Looking for Secrets?

Aside from the fact that there are no longer blank spaces on the map, there are four social trends that have rooted out belief in secrets:

- Incrementalism

- “From an early age, we are taught that the right way to do things is to proceed one very small step at a time, day by day, grade by grade. If you overachieve and end up learning something that's not on the test, you won't receive the credit for it. But in exchange for doing exactly what's asked of you (and for doing it just a bit better than your peers), you'll get an A."

- Risk aversion

- “People are scared of secrets because they are scared of being wrong. By definition, a secret hasn't been vetted by the mainstream. The prospect of being lonely but right—dedicating your life to something that no one else believes in—is already hard. The prospect of being lonely and wrong can be unbearable.”

- Complacency

- “Why search for a new secret if you can comfortably collect rents on everything that has already been done?”

- Flatness

- “Given the assumption [that the world is one homogenous, highly competitive marketplace—as ‘flat’], anyone who might have had the ambition to look for a secret will first ask himself: if it were possible to discover something new, wouldn't someone from the faceless global talent pool of smarter and more creative people have found it already?”

The Case for Secrets

Thiel pushes that secrets will only be found by those who look for them and by believe they are possible in the first place. Believing that secrets exist is an effective truth all in itself:

The actual truth is that there are many more secrets left to find, but they will yield only to relentless searchers. There is more to do in science, in medicine, engineering, and in technology of all kinds. […] But we will never learn any of these secrets unless we demand to know them and force ourselves to look.

The same is true of business. Great companies can be built on open but unsuspected secrets about how the world works... only by believing in and looking for secrets could you see beyond the convention to an opportunity hidden in plain sight.

How to Find Secrets

When thinking about what kind of company to build, there are two distinct questions to ask:

- What secrets is nature not telling you?

- What secrets are people not telling you?

Thiel argues it's easy to assume that natural secrets are the most important as the people who look for them can sound intimidatingly authoritative. But it's actually secrets about people that are relatively under-appreciated: What are people not allowed to talk about? What is forbidden or taboo?

To take this a step further, one could ask: What are people running companies not allowed to say?

The best place to look for secrets is where no one else is looking. So you might ask: are there fields that matter but haven't been standardized and institutionalized? It won't be easy, but it's not obviously impossible: exactly the kind of field that could yield secrets.

What To Do With Secrets

This is where Thiel connects the dots between secrets and startups:

So who do you tell (a secret)? In practice, there's always a golden mean between telling nobody and telling everybody—and that's a company. The best entrepreneurs know this: every great business is built around a secret that's hidden from the outside. A great company is a conspiracy to change the world; when you share your secret, the recipient becomes a fellow conspirator.

He summarizes this: Take the hidden paths.

VII. The Mechanics of Mafia

This chapter covers the dynamics of a company within its own walls, namely, its culture. Thiel is vehemently against the caricature of what typical Silicon Valley companies have become: outrageous perks, interior decorators beautifying the office, human resource consultants to fix policies, and branding specialists to hone on buzzwords. Thiel defines company culture as such:

“Company culture” doesn't exist apart from the company itself: no company has a culture; every company is a culture. A startup is a team pf people on a mission, and a good culture is just what that looks on the inside.

Beyond Professionalism

Thiel maintains that relationships are the most important part of a company. He rejects the idea of people working together who don't even like each other, and despises the idea of free agents checking in and out purely on a transactional basis, and argues it as irrational:

Since time is your most valuable asset, it's odd to spend it on working with people who don't envision any long-term future together. If you can't count durable relationships among the fruits of your time at work, you haven't invested your time well—even in purely financial terms.

At PayPal, he believed that tightly knit companies built on strong relationships would make people not just happier and better at their jobs but also more successful in their careers beyond PayPal. In hiring, they sought candidates who were talented, but more importantly, had to be excited about working specifically with them.

Recruiting Conspirators

Thiel argues that recruiting is a core competency for any company, and as such, should never be outsourced. And because talented people don't need to work for you because they have plenty of options, companies should have a reason why someone would join their company when they could work elsewhere for more money and prestige.

Bad reasons are things like valuable, stock, smart people, and pressing problems, because every company makes these same claims. The good answers are specific to the company. But two general kinds of good answers are answers about your mission and answers about your team.

You'll attract the employees you need if you can explain why your mission is compelling: not why it's important in general, but why you're doing something important that no one else is going to get done.

That said, a great mission is not enough. The recruit who would be most engaged will also wonder, “Are these the kind of people I want to work with?” and you should be able to explain why your company is a unique match for them personally. And if you can't do that, then they're probably not the right match.

Lastly, if you have to fight for perks, they would be a bad addition to the team. After covering the basics like health insurance, the most you can do is promise what no one else can: the opportunity to do irreplaceable work on a unique problem alongside great people.

Tribe of Like-Minded Individuals

Thiel believes that from the outside, everyone in your company should be different in the same way, and his co-founder at PayPal Max Levchin extends this believe that startups should make their early staff as personally similar as possible.

Startups have limited resources and small teams. They must work quickly and efficiently in order to survive, and that's easier to do when everyone share an understanding of the world.

This is an argument not about being similar in how you look or any other superficial dimension. It's about having a similar point of view of how the world ought to be, and equally obsessed about similar things.

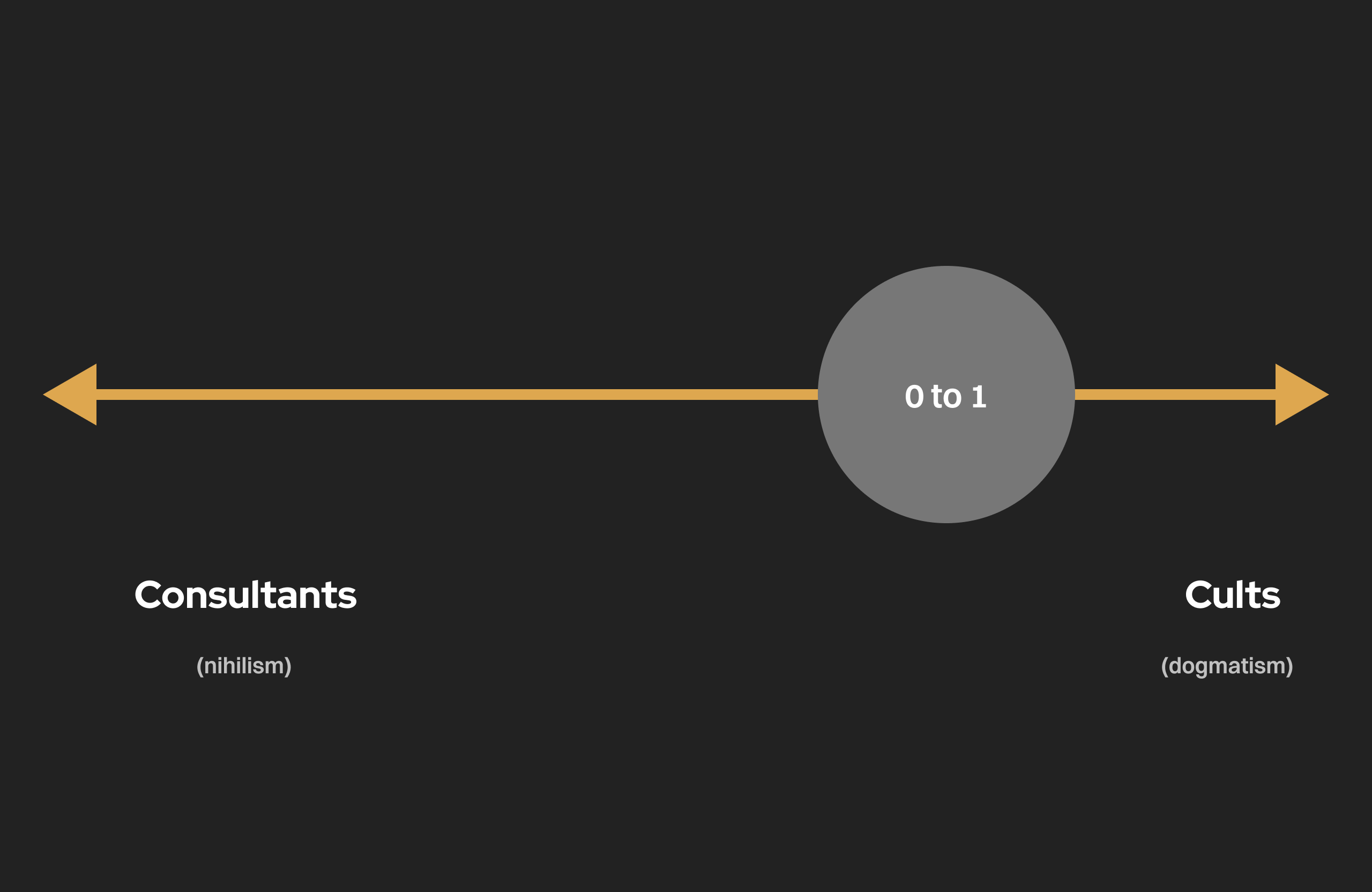

Of Cults and Consultants

There are intense kind of organizations with members who experience strong feelings of belonging and get access to esoteric “truths” denied to ordinary people—these are called cults. The extreme opposite of a cult is a consulting firm like Accenture which lacks a distinctive mission and consultants regularly drop in and out companies without any long-term connection.

Thiel argues that the best startups might be considered slightly less than the extreme kinds of cults. The difference is cults tend to be fanatically wrong about something important, whereas people at a successful startup are fanatically right about something those outside have missed.

This means that you don't need to worry if your company doesn't make sense to conventional professionals. It's better to be called a cult—or even a mafia.

Teams should be different to outsiders in the same way. Having a similar perspective about the world is a powerful lever to get people to do difficult things together, and more importantly, develop strong relationships. Who we spend time with is among the biggest investments we can make in life, so choose wisely. In this instance, better to be misunderstood to conventional people; better to be a cult than consultants.

VIII. If You Build It, Will They Come?

The short answer is no. Thiel argues that technology companies severely underestimate the importance of distribution—the catchall term for everything it takes to sell a product. Even businesspeople underestimate the importance of sales, because there is a systematic effort to hide it at every level of every field in a world secretly driven by it.

Instead of making companies solely about a product so great it sells itself, he argues that “it's better to think of distribution as something essential to the design of your product:”

If you've invented something new but you haven't invented an effective way to sell it, you have a bad business—no matter how good the product.

How to Sell a Product

He starts this section with a banger that most people would be uncomfortable to admit:

Superior sales and distribution by itself can create a monopoly, even with no product differentiation. The converse is not true.

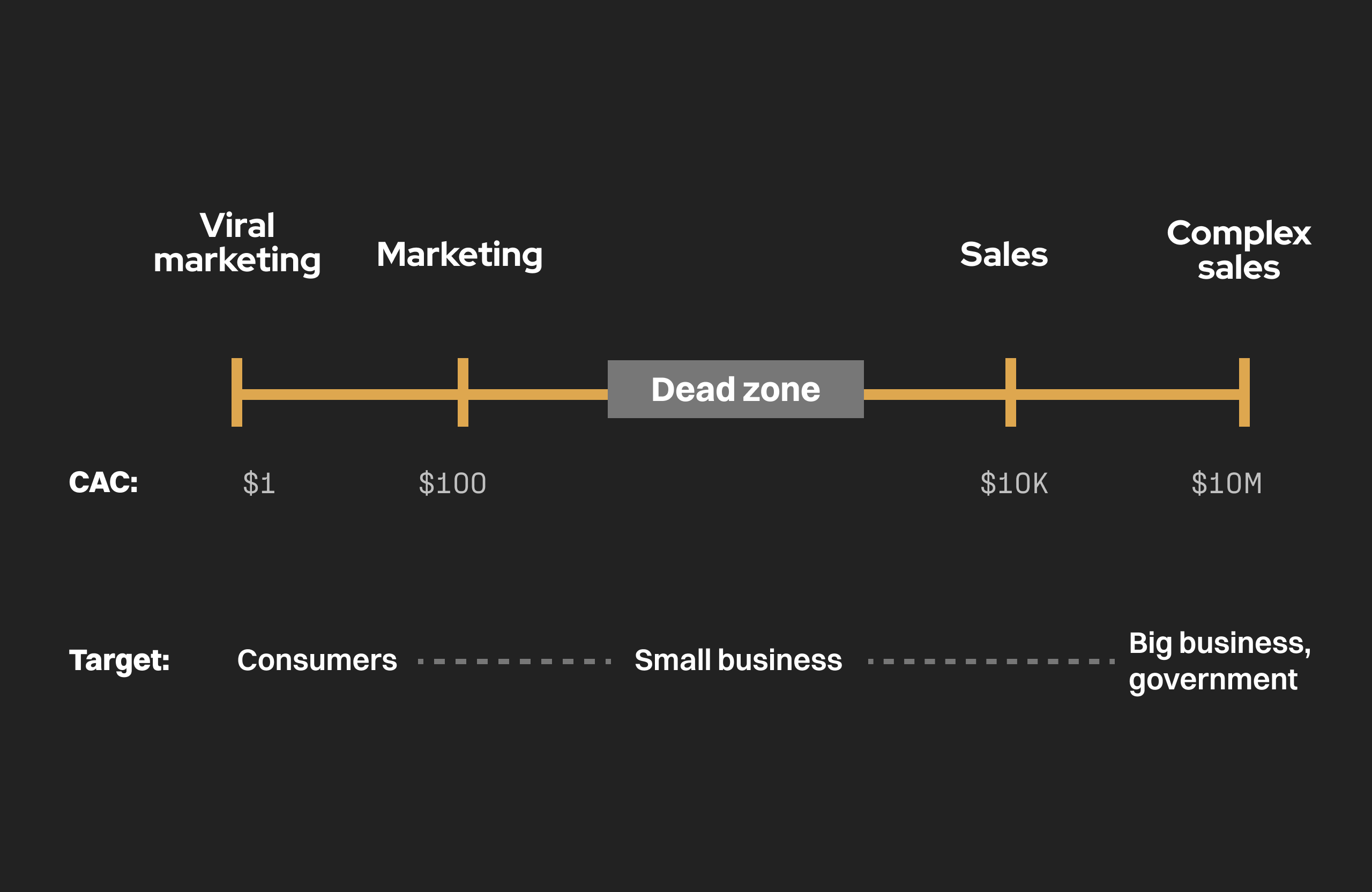

There are two metrics that set limits for effective distribution: the total net profit you earn on average over the course of your relationship with a customer (Lifetime Value or LTV) must exceed the amount you spend on average to acquire a new customer (Customer Acquisition Cost or CAC). In general, the higher the price of your product, the more you have to spend to make a sale and the more it makes sense to spend it.

There is a continuum for sales at a company.

- Complex Sales

- “If your average sale is seven figures or more, every detail of every deal requires close personal attention: it takes months to develop the right relationships, you might make a sale only once every year or two, and you usually have to follow up during installation and service the product long after the deal is done. It's hard to do but this kind of complex sales is the only way to sell some of the most valuable products.”

- “Good enterprise sales strategy starts small, as it must: a new customer might agree to become your biggest customer, but they'll rarely be comfortable signing a deal completely out of scale with what you've sold before.”

- Personal Sales

- “Most sales are not particularly complex average deal sizes might range between $10,000 and $100,000. The challenge here isn't about how to make any particular sale, but how to establish a process by which a sales team of modest size can move the product to a wider audience.”

- Distribution Dead Zone

- “In between personal sales (salespeople obviously required) and traditional advertising (no salespeople required) there is a dead zone.”

- If you're selling a $1000 a year product to a specific niche, there might be no good distribution channel to reach the small business that might buy it: advertising would be too broad (targeting would be too hard) or too inefficient (you won't convince a small owner to part with $1,000 a year). The product needs a personal sales effort but at that price point, you don't have resources to send an actual person to talk to every prospective customer.

- Marketing and Advertising

- This works for relatively low-priced products that have mass appeal but lack any method for viral distribution.

- P&G can't afford to pay salespeople to go sell detergent door-to-door, but they can produce TV commercials, print coupons, and design its product boxes to attract attention.

- Advertising can work for startups too but only when your customer acquisition costs and customer lifetime value make every other distribution channel uneconomical.

- Viral Marketing

- “A product is viral if its core functionality encourages users to invite their friends to become users too. [...] This isn't just cheap—it's fast, too. If every new user leads to more than one additional user, you can achieve a chain reaction of exponential growth. The ideal viral loop should be as quick and frictionless as possible.”

- “Whoever is first to dominate the most important segment of a market with viral potential will be the last mover in the whole market.”

The Power Law of Distribution

Just like anything, distribution follows a power law of its own: one of these methods is likely to be more powerful than every other combined for any given business. This is counterintuitive for most entrepreneurs who assume that more is more, when in truth, the kitchen sink approach doesn't work.

Most businesses get zero distribution channels to work: poor sales rather than bad product is the most common cause of failure. If you can just get one distribution channel to work, you have a great business. If you try for several but don't nail one, you're finished.

Everybody Sells

Thiel ends this chapter with a quip:

Everybody has a product to sell—no matter whether you're an employee, a founder, or an investor. It's true even if your company consists of just you and your computer. Look around. If you don't see any salespeople, you're the salesperson.

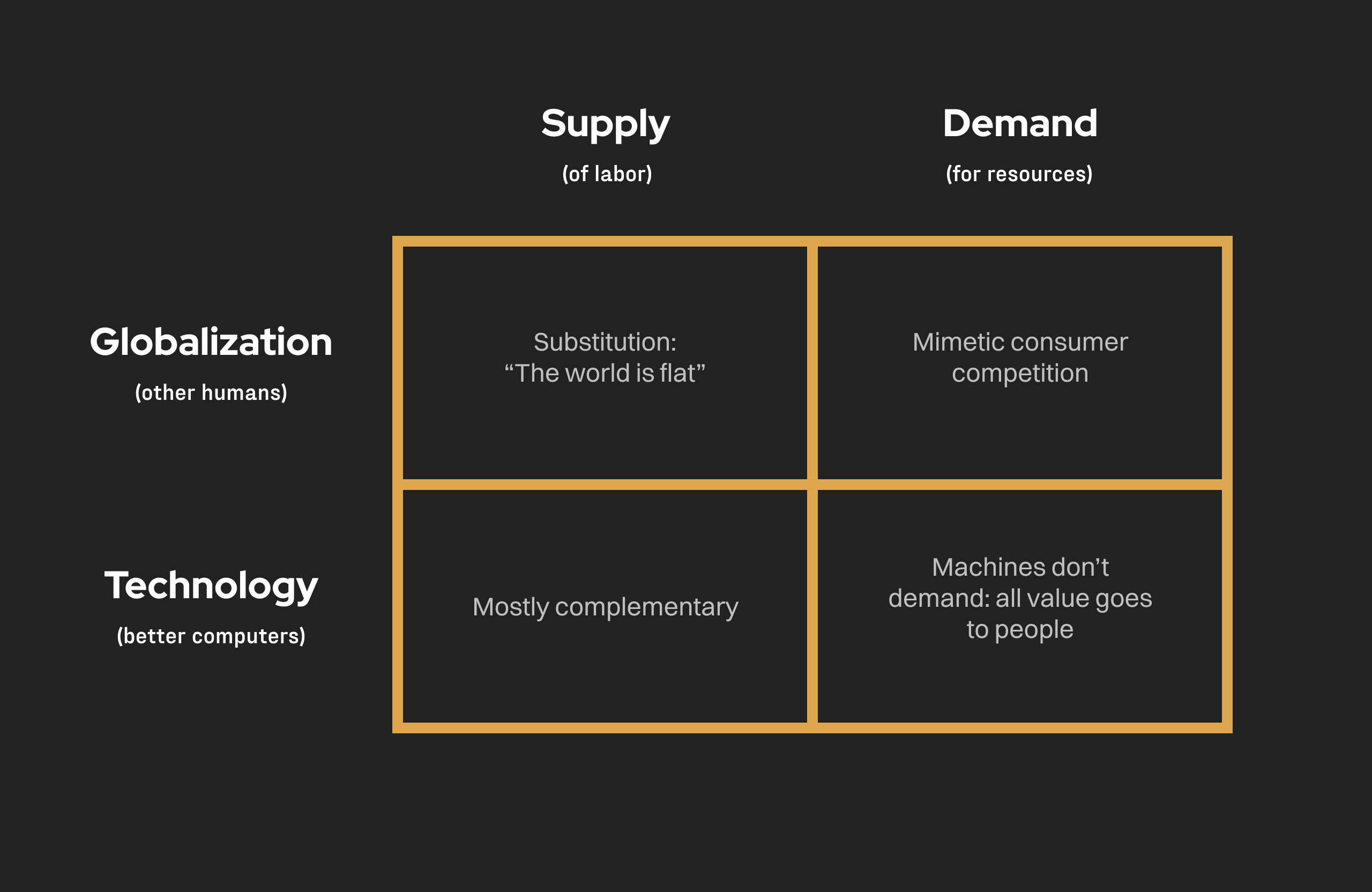

VIII. Man and Machine

This chapter may be more nascent in 2024 than when the book was published in 2014. Thiel argues that technology is not meant to be seen as a rival, but as a tool. And the ones who use technology to empower people, and not replace them, are the ones that will build great businesses.

Computers are complements for humans, not substitutes. The most valuable businesses in the coming decades will be built by entrepreneurs who seek to empower people rather than try to make them obsolete.

Substitution vs. Complementarity

Thiel argues that using technology over globalization is a more compelling way of creating value. This is because people don't just compete in the labor market, they also compete for similar resources. If technology is used properly, all the value accrues to humans, without competing for the same resources they do. Thus, humans and computers don't have to compete because they are categorically different in what they do as they are good at fundamentally different things:

People have intentionality—we form plans and make decisions in complicated situations. We're less good at making sense of enormous amounts of data. Computers are exactly the opposite: they excel at efficient data processing, but they struggle to make basic judgments that would be simple for any human.

Thiel makes the case that outsourcing the more manual data processing tasks to computers gives room for humans to focus on what they're uniquely good at. To think of humans as purely widgets that compete against technology is to place humans in the lowest common denominator.

Complementary Businesses

A thought exercise that Thiel wondered about after they sold PayPal is the man-machine solution: “if humans and computers together could achieve dramatically better results than either could attain alone, what other valuable businesses could be built on this core principle?”

Computers can find patterns but ultimately, they can't interpret complex behaviors and he argues that actionable insights can only come from a human analyst. Even with more advanced technology in 2024 than we have in 2014, I agree with this premise. The technology may be more powerful and smarter, but so long as computers can't take responsibility and imagine for themselves without a prompt, they can't ultimately replace humans. His business conclusion to this is:

The most valuable companies in the future won't ask what problems can be solved with computers alone. Instead, they'll ask: how can computers help humans solve hard problems?

Ever-Smarter Computers: Friend or Foe?

Thiel argues that “Strong AI” or computers that eclipse humans in every important dimension is a problem for the 22nd century. He says that even if it was possible, that indefinite fears about the far future shouldn't stop us from making definite plans today.

There are extreme beliefs on both sides — Luddites on one end that we shouldn't build the computers that might replace us, and crazed futurists that argue we should. He argues that these two positions are mutually exclusive but are not exhaustive:

...there is room in between for sane people to build a vastly better world in the decades ahead. As we find new ways to use computers, they won't just get better at the kinds of things people already do; they'll help us do what was previously unimaginable.

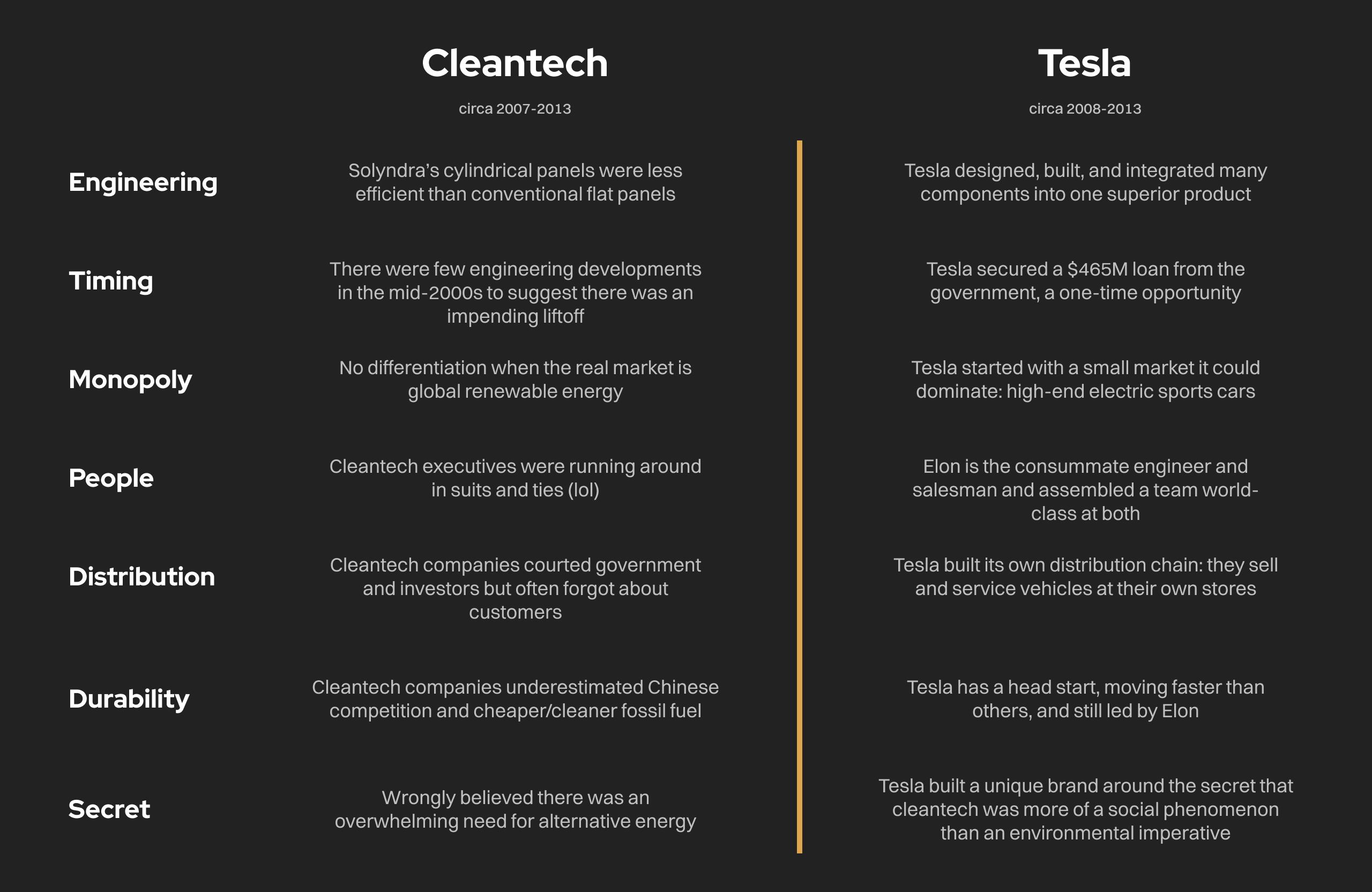

IX. The Seven Questions

The next chapter is really about why cleantech didn't work in the 2010s analyzed through the seven questions asked in Zero to One. Thiel uses these questions as a filter that every business must answer:

- The Engineering Question

- “Can you create breakthrough technology instead of incremental improvements?"

- “Companies must strive for 10x better because merely incremental improvements often end up meaning no improvement at all for the end user. Only when your product is 10x better can you offer the customer transparent superiority.”

- The Timing Question

- “Is now the right time to start your particular business?”

- “Entering a slow-moving market can be a good strategy, but only if you have a definite and realistic plan to take it over.”

- The Monopoly Question

- “Are you starting with a big share of a small market?”

- “Customers won't care about any particular technology unless it solves a particular problem in a superior way. And if you can't monopolize a unique solution for a small market, you'll be stuck with vicious competition.”

- The People Question

- “Do you have the right team?”

- Founders Fund has a blanket rule: pass on any company whose founders dressed up in suits for for pitch meetings (lol).

- “The best sales is hidden. There's nothing wrong with a CEO who can sell, but if he actually looks like a salesman, he's probably bad at sales and worse at tech.”

- The Distribution Question

- “Do you have a way to not just create but deliver your product?”

- “Selling and delivering a product is at least as important as the product itself.”

- The Durability Question

- “Will your market position be defensible 10 and 20 years into the future?”

- “Every entrepreneur should plan to be the last move in her particular market. That starts with asking yourself: what will the world look like 10 and 20 years from now, and how will my business fit in?”

- The Secret Question

- “Have you identified a unique opportunity that others don't see?”

- “Great companies have secrets: specific reasons for success that other people don't see.”

The Myth of the Social Entrepreneurship

Because Feel Eternity also thinks about philosophy, this is one of my favorite sections in the book. Thiel holds the position that, “social entrepreneurs aim to combine the best of both worlds (for-profit motive and non-profit interest) and ‘do well by doing good.’ Usually they end up doing neither.” He argues that “Whatever is good enough to receive applause from all audiences can only be conventional.”

If trying to tiptoe this line and be ambiguous isn't good for society, Thiel counters it back to the singular question:

Doing something different is what's truly good for society—and it's also what allows a business to profit by monopolizing a new market. The best projects are likely to be overlooked, not trumpeted by a crowd; the best problems to work on are often the ones nobody else even tries to solve.

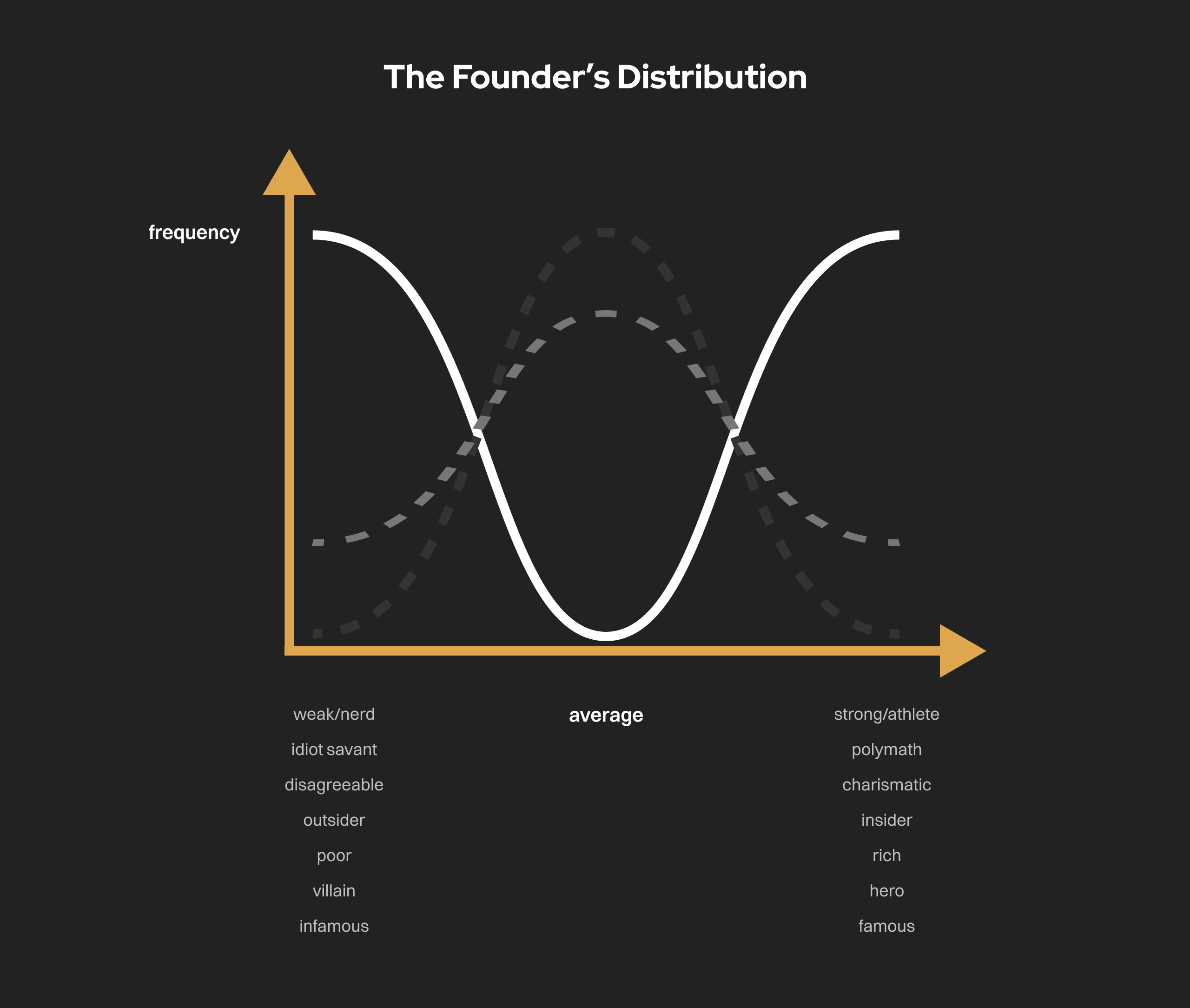

X. The Founder's Paradox

The chapter covers why Thiel believes it's more powerful but at the same time more dangerous for a company to be led by a distinctive individual instead of an interchangeable manager.

First, Thiel argues that most people who become successful founders aren't just fat-tailed in a normal distribution of traits, which feels like the more intuitive way to think of these kinds of people in comparison with the general population. He argues that the founder distribution are simultaneously insiders and outsiders, and when they do succeed, they attract both fame and infamy. The distribution is actually convex—they are usually an extreme combination of both sides.

Are they actually extreme as they seem? Do they exaggerate their own characteristics? Is it possible that everyone else exaggerates them? Instead of saying these things are exclusive, Thiel argues that they can all exist at the same time. Being actually different can lead to developing extreme traits, which can lead to them exaggerating these traits, which lead to others exaggerating them, making them actually different—a positive feedback loop that can reinforce each other.

Because of this extreme persona, Thiel makes a point that founders make for an effective scapegoat: on one hand, they are powerless to stop their own victimization; on the other hand, as the one who can defuse conflict by taking the blame, they are the most powerful member of the community. Thiel captures this with a thought: “Perhaps every modern king is just a scapegoat who has managed to delay his own execution.”

The Return of the King

Thiel illustrates this dichotomy by using Steve Jobs who founded Apple, got kicked out by his own board of directors, only to be asked to come back and eventually turn it from a failing company into the most valuable company in the world (as of this writing, is still accurate 10 years after the publishing of Zero to One, with a market cap of $3.3 trillion).

Thiel's argument is that Jobs' return signifies something in companies that create new technologies: that they resemble feudal monarchies rather than organizations that are supposedly modern. A unique founder:

- can make authoritative decisions

- they inspire strong personal loyalty

- they plan ahead for decades

Thiel encapsulates his point:

The lesson for business is that we need founders. If anything, we should be more tolerant of founders who seem strange or extreme; we need unusual individuals to lead companies beyond mere incrementalism.

The lesson for founders is that individual prominence and adulation can never be enjoyed except on the condition that it may be exchanged for individual notoriety and demonization at any moment—so be careful.

Essentially, the founder is the scapegoat—paradoxically the most powerful person in a company because of their influence and authority, but also the one who will be blamed and sacrificed to restore order. His lesson is that we need founders who create new things, and just as important, founders need to be careful not to believe their own myth because praise can turn into demonization just as quickly.

Conclusion: Stagnation or Singularity

Thiel summarizes the four possible futures of humanity as written by philosopher Nick Bostrom:

- Recurrent Collapse

- Never-ending alternation between prosperity and ruin.

- Plateau

- The whole world will converge toward a plateau of development similar to the life of the richest countries today.

- Extinction

- A collapse so devastating that we won't survive it.

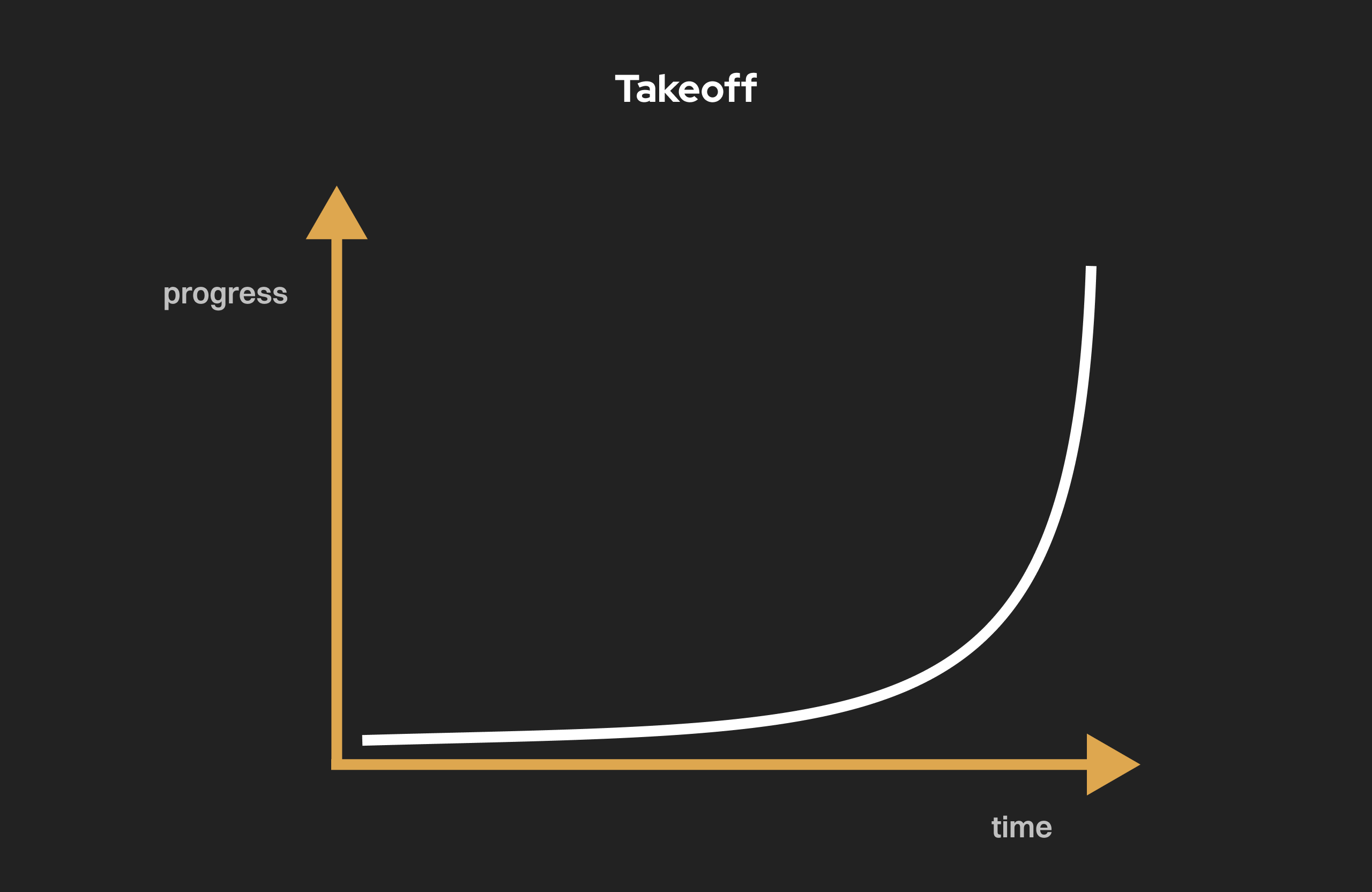

- Takeoff

- Accelerating takeoff toward a much better future.

He evaluates each one and argues against the first three, and especially warns against stagnation as it collapse into extinction. He argues the only way out is the fourth scenario in which we create new technology to make a much better future. The most dramatic version of this outcome is the Singularity, a future so powerful that it transcends the limits of our own understanding. Thiel ends with this thought:

The future won't happen on its own. What the Singularity looks like matters less than the stark choice we face today between the two most likely scenarios: nothing or something. It's up to us. We cannot take for granted that the future will be better, and that means we need to work to create it today.

[...] Our task is to find ways to create the new things that will make the future not just different, but better—to go from 0 to 1. The essential first step is to think for yourself. Only by seeing the world as as anew, as fresh and strange as it was to the ancients who saw it first, can we re-create it and preserve it for the future.

Takeaways

Zero to One is a compelling book from a controversial author. No matter one's opinion on Thiel and his politics, it's hard to deny that he practices what he preaches: rejection of conventional beliefs and long-term execution of plans.

He has the track record to back it, through the founding of PayPal and Palantir, being the first outside investor in Facebook, and Founders Fund having a portfolio that boasts investments in SpaceX, DeepMind, Airbnb, and Stripe among others. Outside of business, in a huge surprise at the time, he publicly backed Donald Trump who eventually won the 2016 election, and used $10M of his own money in legal expenses against Gawker, holding a decade-long vendetta against the gossip blog for publicly outing his sexuality, ultimately bankrupting the publication.

Ten years after Zero to One's publishing, the book has strongly held up, maybe even feels more prescient now that the artificial intelligence race is full steam ahead, Google facing an antitrust case with a federal judge labeling them a monopoly, and much of the tactics hold up such as starting small and monopolizing a market, sales being as important as product, and focusing on the singular things that create power laws.

My opinion of the book is that it's refreshing to read from the perspective of someone who has proven to be repeatedly successful go against conventional truths one by one. Thiel clearly explain himself in detail his thought process as to why it's not just wrong but why the converse may actually be more right. It's also filled with humorous jabs (comparing hipsters to The Unabomber, not funding anyone pitching in a suit and tie, and calling out how nerds discriminate against salesmen), and he doesn't hold back by name-checking people and companies directly.

He doesn't say it directly, but may be the best part of this book is it's filled with references in literature (Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet, Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings) and his philosophy, as influenced by René Girard, around mimetic theory and the scapegoat mechanism. This is unconventional as far as business books typically go and they certainly don't go in-depth and esoteric the way he does, giving direct examples of how he operated his own startups in practice, while still grounding it in business terms and technological advancements.

For builders, these are the 10 most important takeaways I've found:

- Think for yourself. Don't just accept conventional truths.

- Don't compete. Be a monopoly of one.

- Look for valuable secrets. They're everywhere around us especially hidden in what people are not allowed to talk about.

- Be a definite optimist—believe the future can be better if you work at making it better.

- Understand power laws. Single-minded pursuit wins over diversification.

- To win in technology, your solution must be 10x better, not 2x better.

- Distribution (which includes sales) matter just as much as product.

- See technology as a complementary, not a rival.

- Be tolerant of founders. And accept that there are steep costs of being a founder.

- Takeoff is the best possible scenario for humanity. We must work on it today.

These are harder to do in practice. But Zero to One offers a strong roadmap for how to build the future. In Grandmaster Jose Raul Capablanca's words:

You must study the endgame before everything else.

♾️